Last week, I encountered two events related to research and innovation. The University of San Diego has published a visual resource guide titled “Business Innovation and Leadership Lessons From 8 Revolutionary Entrepreneurs” which lists the most important measures of innovation that companies use. It is based on a survey carried out by PWC in 1200 companies (Fig. 1). I also attended a workshop organized by a Horizon 2020 project on RRI (Responsible Research and Innovation) which discussed, among other things, the impact of thematic elements of RRI on innovation, namely (1) public engagement, (2) open science, (3) gender equality, (4) ethics and (5) science education.

Comparing the innovation metrics that companies use and the thematic elements of RRI, it seems that there is a substantial gap, and RRI would have a very limited impact on the innovation performance of companies, both in the demand (sales, customer satisfaction) and supply (time to market, pipeline of ideas and products) for innovation. When reflecting on the impact of IRR on innovation performance, two questions arise spontaneously: (a) Is there an impact of RRI actions on the areas that companies measure to assess their innovation performance, and (b) to what extent is the RRI aligned with current EU research and innovation strategy for smart specialisation.

Fig. 1: Seven most important metrics for measuring innovation

Source: San Diego University [1]

For H2020, “Responsible Research and Innovation (RRI) implies that societal actors (researchers, citizens, policymakers, business, third sector organisations, etc.) work together during the whole research and innovation process in order to better align both the process and its outcomes with the values, needs and expectations of society”. RRI as key-action of the ‘Science with and for Society’ objective of H2020 is promoted by actions on public engagement, open access, gender, ethics, and science education [2]. But which is the potential impact of these five RRI drivers on the metrics of innovation?

Public engagement in RRI is about co-creating with citizens and civil society organisations, and also bringing on board the widest possible diversity of actors that would not normally interact with each other, on matters of science and technology [3]. There is a wide literature on user engagement and innovation, started from the work of Von Hippel on democratizing innovation [4]. Also, there is plenty of evidence that user engagement affects positively all metrics of innovation highlighted by the San Diego University, both at the creativity (innovation pipeline) and the market side of innovation (sales, customer satisfaction, market share).

Open science in RRI is mainly about ‘open access’ publications and making research findings available free of charge for readers. It is illustrated by the general principle for open access to scientific publications in Horizon 2020 and the pilot for research data [5]. Open access is just a small step towards open science. It is a state-led business model for academic journals, in which the producer than the consumer undertakes the publication costs. Has open access any impact on the 7 most important innovation metrics presented in Fig. 1? There is little evidence on this, and as Borzacchiello and Craglia point out “The causal link between accessibility to resources and economic development is frequently claimed, but not always supported by evidence-based studies” [6]. Open science, thus scientific production without Intellectual Property Rights, would have a cataclysmic impact on innovation and all its metrics. But clearly, the intention of RRI does not go that far.

Gender equality in RRI and Horizon 2020 is promoted in all parts of the Work Programme, ensuring a more balanced approach to research and innovation [7]. But how gender equality is placed with respect to innovation performance? Could an equal gender composition of research and innovation teams improve those 7 metrics of innovation? Based on a review of the current literature on gender and innovation, Alsos, Hytti, and Ljunggren argue that innovation is a gender-biased phenomenon. There is research studying differences between individuals and how gender is embedded in processes, meanings and experiences. For example, studies have shown that male researchers are more likely than female researchers to engage in industry cooperation or “academic mothers” are less likely to patent, implying that gender and family responsibilities impede women’s ability to innovate [8]. Much is depending on the meaning of “gender equality”. If it is interpreted as gender quotas (50-50 percent of men and women in research and innovation teams) then it turns to a constraint, which is negative to innovation performance and metrics. On the contrary, if it is understood as equal opportunities for men and women, selecting the best regardless gender, equality becomes a propeller to innovation, equal to skills, competence, and qualifications. Many interviews on this subject highlight that “competence matters more than gender”; “competence and knowledge is more important than gender”; “the competence must be the most important thing”; selecting researchers should be gender-neutral, depending on roles and industry [9].

Ethics, for all research funded by H2020, ethics is an integral part from start to finish, and ethical compliance is considered essential to achieve research excellence [10]. For some current topics in AI and robotics, ethics are very important and critical, such as algorithm bias, lethal autonomous weapon systems, research with humans, data privacy. However, when it comes to innovation metrics, ethics works as a constraint rather than a propeller.

Science education is about building capacities and developing innovative ways of connecting science to society. It is a priority under Horizon 2020, expected to make science more attractive, increase the demand and open further innovation activities [11]. This is somehow common sense and self-fulfilling prophecy; that science education is a driver to research and innovation, and the challenge is to define the best science education mix to improve research and innovation performance.

RRI was an important funding line within the H2020 “Science with and for Society” (SwafS), which had a budget of 462 million Euro for the entire period of H2020 [12]. I am not aware how much of the SwafS budget was spent on RRI. Yet, apart from citizen engagement in innovation, which introduces a new innovation paradigm based on user engagement, crowdsourcing, extended collaboration, digital innovation, the other four elements of RRI range between common sense and ethics, with a rather minimal impact on innovation performance. Four out of five RRI constituting elements are closer to ideology and policy objectives than evidence-based principles that sustain innovation performance with impact on innovation metrics.

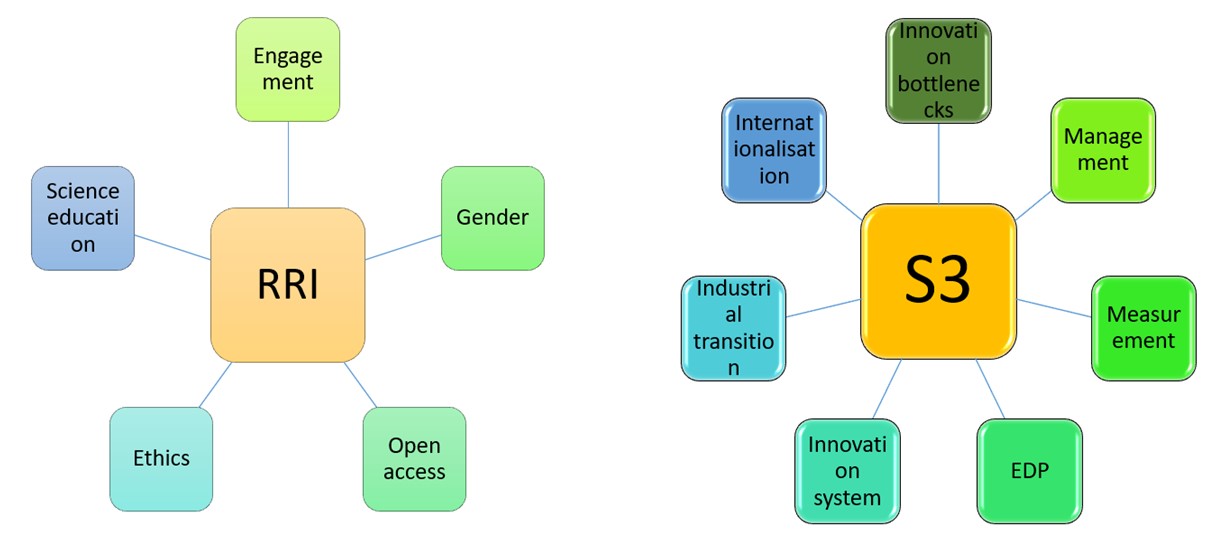

If RRI is closer to policy objectives than to an evidence-based innovation driver, then should we seek its link with the current EU research and innovation policy, introduced in 2012, the research and innovation strategy for smart specialisation (S3 or RIS3).

In the consecutive work programmes of SwafS, the link between RRI and S3 appears quite late, towards the end of H2020. The 2014-2015 work programme makes no reference to smart specialisation. In the 2016-2017 work programme, smart specialisation is mentioned in the context of the quadruple helix policy (SwafS-05-2017) and for the first time a link appears between RRI, S3, and public engagement (SwafS-13-2017). Then, in the 2018-2020 work programme, there are many references on the synergies between RRI and S3, the mapping of R&I territorial ecosystems, RRI and the Smart Specialization Platform. Projects such as TeRRIFICA, TeRRItoria, SeeRRI, ONLINE-S3 and SEiSMIC are mentioned in this regard. Alignment, however, between RRI and S3 was not as easy as the building blocks of their objectives differ considerably (Fig. 2).

Fig 2: RRI and S3 objectives: divergence than alignment

Social science research and in particular the SwafS programme could be an important driver supporting the Smart Specialisation Strategy, especially as regards the methodologies of the Entrepreneurial Discovery Process, innovation monitoring and measurement, mapping innovation bottlenecks, and other key principles of good governance for a Smarter Europe, through innovation, digitisation, economic transformation and support to small and medium-sized businesses [13]. In the lifespan of H2020, this alignment has not been reached or reached to a very small extent. RRI is a good case of what should be done better. Research is very welcome to identify drivers of higher innovation performance. But this should go without binding principles and let data and evidence lead the way. If policy is the aim then objectives should align across policy fields.

In the new Horizon Europe and the European Commission’s proposal for the next Framework Programme for Research and Innovation (2021-2027) with a proposed budget of 94.1bn, the link between research and innovation policy (Horizon Europe) and cohesion policy (S3) should be better organized. Not only in terms of common areas and subjects that could be addressed by research. But, also in terms of the assessment framework that brings research closer to innovation performance. For instance, a revision of the current research proposals evaluation should pay more attention to previous scientific record of research teams and the availability and intensity of effort of the research staff. This assessment block on previous scientific record, in which we can find elements of open access and innovation measurement, could replace the foresight on impact, and the wishful thinking which generally contains the current estimate of impact.

References

- [1] San Diego University, School of Business

https://www.sandiego.edu/blogs/business/detail.php?_focus=76185 - [2] H2020 – Responsible Research and Innovation

https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/en/h2020-section/responsible-research-innovation - [3] H2020 – Public Engagement in Responsible Research and Innovation

https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/node/766 - [4] Von Hippel, E. (2005). Democratizing innovation: The evolving phenomenon of user innovation. Journal für Betriebswirtschaft, 55(1), 63-78.

- [5] H2020 – Open Science (Open Access)

https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/node/1031 - [6] Borzacchiello, M. T., & Craglia, M. (2012). The impact on innovation of open access to spatial environmental information: A research strategy. International Journal of Technology Management, 60(1-2), 114-129.

- [7] H2020 – Promoting Gender Equality in Research and Innovation,

https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/node/797 - [8] Alsos, G. A., Hytti, U., & Ljunggren, E. (2013). Gender and innovation: state of the art and a research agenda. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 5(3), 236-256.

- [9] Ljunggren, E., Alsos, G. A., Amble, N., Ervik, R., Kvidal, T., & Wiik, R. (2010). Gender and innovation. Learning from regional VRI-projects. NF-report, 2, 2010, p. 83.

- [10] H2020 – Ethics, https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/node/767

- [11] H2020 – Science Education, https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/horizon2020/node/795

- [12] Horizon 2020 Budget, http://cerneu.web.cern.ch/horizon2020/budget

- [13] Regional Development and Cohesion Policy beyond 2020: The New Framework at a glance

https://ec.europa.eu/regional_policy/en/2021_2027/