In recent days we have seen a series of initiatives to combat the pandemic with data, web platforms for research sharing, and models for simulation and forecasting. But how successful can these efforts be? What digital systems can strengthen and accelerate research and innovation in various fields of science and technology?

Digital platforms, sharing research and innovation

The European Commission launched the European COVID-19 Data Platform to enable the rapid collection and sharing of available research data. The platform is part of the ERAvsCorona Action Plan. It brings together relevant datasets submitted to EMBL-EBI and other major centres for biomedical data with the aim to facilitate data sharing and analysis, and to accelerate coronavirus research.

Some Horizon 2020 projects move toward the same direction. The EXSCALATE4CoV, for instance, is a Horizon 2020 project that uses an intelligent supercomputing platform to drive fast virtual identification and repurposing of known drugs or proprietary/commercial candidate molecules for Covid-19. The rationale is that a vaccine is likely to take 12 to 18 months, while a new drug could be a decade away as the average timeline for a new drug is 12 years to be approved for wide use. In contrast, repurposing existing drugs for other conditions can be a shortcut. Repositioning is a form of organised serendipity: doing research for something and you find something useful in another field far away from the initial field of research. It is not unusual for a drug to have unexpected benefits in other areas. Or drugs that didn’t work for their original purpose may be effective for other areas.

IBM to help researchers generate potential new drug candidates for COVID-19 opened the bluemix.net and offers a novel AI generative frameworks to three COVID-19 targets and explore drug candidates. Over the last two years, IMB researchers have been developing generative frameworks that create novel peptides, proteins, drug candidates, and materials. Applying this methodology to generate drug-like molecule candidates for COVID-19 targets, it is expected that by releasing these novel molecules, the research and drug design communities will accelerate the process of identifying promising new drug candidates for coronavirus and potential similar, new outbreaks.

OECD launched the 2nd phase of the Going Digital project to help countries implement an integrated policy approach to the digital transformation, especially through the Going Digital Toolkit. A report has been also published on the digitalisation of science, technology and innovation [1] arguing that “Digitalisation is bringing change to all parts of science, from agenda setting, to experimentation, knowledge sharing and public engagement. To achieve the promise of open science research budgets need to account for the increasing costs of managing data. Greater policy coherence and trust between research data communities are needed to increase sharing of public research data across borders (p. 17). Moreover, “AI is being used in all phases of the scientific process, from automated extraction of information in scientific literature, to experimentation (the pharmaceutical industry commonly uses automated high-throughput platforms for drug design), large-scale data collection, and optimised experimental design” (p.25).

Democratising innovation

The turn towards digital innovation started with the new millenium. A landmark has been the publication of Democratizing Innovation by Eric Von Hippel in 2005 [2]. He described the convergence of innovation and ICTs, pointing out that “Innovation is rapidly becoming democratized. Users, aided by improvements in computer and communications technology, increasingly can develop their own new products and services. These innovating users -both individuals and firms – often freely share their innovations with others, creating user innovation communities and a rich intellectual commons” (p. 13). Empowering users, he argues, bringing lead users into the innovation process, and adopting a user-centric innovation approach offers significant advantages over manufacturer-centric innovation. Crowdsourcing innovation marks the turn towards a sharing innovation paradigm and illustrates the widening of collaboration within systems of innovation enabled by Web and Internet technologies.

Navigating the digital future of innovation

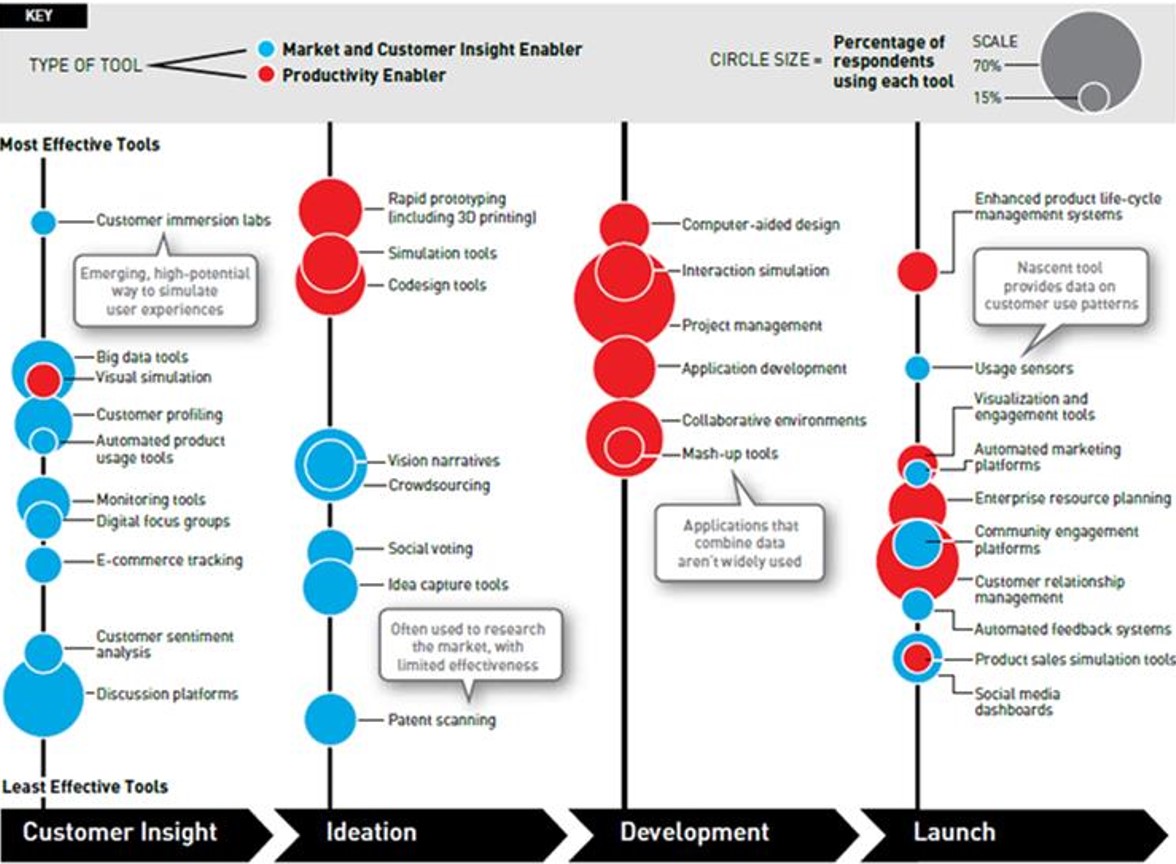

A survey on the use of digital tools in the innovation process has been carried out by Jaruzelski, Loehr, and Holman entitled “The global innovation 1000: Navigating the digital future” [3]. The survey that took place in 2013, highlighted how companies deploy digital tools, analyse usage data and simulate user experience to improve the usability and serviceability of new products. One thousand public companies from around the world that spent the most on R&D were identified and an online survey was conducted. About 400 senior managers and R&D professionals described how digital tools were being used in four successive stages of innovation: customer insight, ideation, development, and launch. They were also asked to assess the effectiveness of digital tools and factors of success.

34 digital tools were identified, 19 within the group of market and customer insight enablers (marked in blue) and 15 in the group of productivity enablers (marked in red). The most used tools per stage are discussion platforms, customer profiling, and big data analytics in the customer insight stage; co-design, rapid prototyping, and crowdsourcing in the ideation stage; project management, CAD and collaborative environments in the development stage; and CRM, ERP, and social media dashboards in the launch stage. A general trend in usage is the transition from established productivity tools towards tools that engage users and customers and create platforms and collaborative environments. In terms of effectiveness big data analytics, simulation and codesign are among the most effective.

The Digital Tool Landscape from “The Global Innovation 1000: Navigating the Digital Landscape” by Jaruzelski, Loehr, and Holman. © 2013 PwC.

Platforms become dominant in the innovation landscape

There is a clear trend to support innovation with digital platforms, data sharing, and user experience. But why does this happen? Which are the advantages of digital platforms with respect to other digital tools, applications and media?

The platform is not a tool that you use. It is a structure on which people or organisations stand to do something else. Some platforms act as magnets for individuals and organisations, creating ecosystems of organisations interacting with others and their environment (the platform). Many platforms are the building blocks (technologies, products and services, infrastructure) on top of which organisations develop inter-related products, technologies and services [4]. But equally, platforms are collaborative business models based on technology and collaboration. A platform is “a plug-and-play business model that allows multiple participants (producers and consumers) to connect to it, interact with each other and create and exchange value” [5].

Platform-based ecosystems are created when an organisation launches a platform that becomes the foundation for products and services of other organisations. Gawer and Cusumano [6] called this relationship ‘platform leadership’, a strategy that enables organisations to exert influence over the direction of innovation in industry by engaging other organisations in a joint effort for complementary products. Industry-wide platforms offer resources that third party organisations can use to develop their own complementary products, technologies, or services. They are foundations for setting up ecosystems of organisations that share resources, knowledge or access to markets [7]. Working with an industry-wide platform typically results in a two-part structure: on the one side, there is the specific solution that is hosted on the platform, and on the other side, there is the platform with its infrastructure, hardware, software and data that organises collaboration within an ecosystem of organisations.

A related concept within the platform ecosystems literature concerns ‘technology ecosystems’, also known as ‘digital ecosystems’ or ‘software ecosystems’. While closely related to the platform stream literature this perspective predominantly considers ecosystems in the context of digital infrastructures, which are shared, unbounded, heterogeneous, open, or evolving socio-technical systems comprising an installed base of diverse information technology capabilities and their user [8].

Externalities and other advantages

Thus, platforms differ from other digital tools and applications because of their ability to create ecosystems. In platform- ecosystems, the ecosystem does not precede the platform but goes hand in hand with the deployment and population of the respective platform.

Once a platform ecosystem is created on a digital platform, three types of advantages follow: externalities, engagement for collaboration, and awareness [9]. The platform is the enabler, and the ecosystem is the provider of externalities or other advantages. An externality is a value from an activity freely received by unrelated organisations. It is a value external to market transactions. Von Hippel, in his book Free Innovation [10], dedicated to the free and user innovation research community, proposes the term ‘free innovation’ for such externalities. “Free innovation involves innovations developed and given away by consumers as a “free good,” with resulting improvements in social welfare. It is an inherently simple, transaction-free, grassroots innovation process engaged in by tens of millions of people. As we will see, free innovation has very important economic impacts but, from the perspective of participants, it is fundamentally not about money.” (p. 1).

In platform ecosystems, externalities derive from network effects and the large number of complementors on the platform. The Internet is full of externalities and ‘free lunch’ supplies. Methods and procedures embedded in online applications are freely offered to users to solve problems. They can improve skills and the decision-making capacity, can engage in the governance of complex systems by roadmaps and digitally guided procedures, provide learning and capacity development. This ‘digital empowerment’ is not based on having skills, but on having access to networking, communication and cooperation. It is a network effect within digitally supported ecosystems.

[1] OECD (2020). The Digitalisation of Science, Technology and Innovation: Key Developments and Policies. OECD Publishing, Paris.

[2] Von Hippel, E. (2005). Democratizing Innovation. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

[3] Jaruzelski, B., J. Loehr, and R. Holman (2013). The global innovation 1000: Navigating the digital future. Business and Strategy, No 73, pp. 33-45.

[4] Gawer, A. (2010). The organization of technological platforms. In: Nelson Phillips, Graham Sewell, Dorothy Griffiths (eds) Technology and Organization: Essays in Honour of Joan Woodward. Research in the Sociology of Organizations, Vol. 29, Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp.287 – 296.

[5] Castellani, S. (n.a.). Everything you need to know about Digital Platforms.

[6] Gawer, A., and Cusumano, M. A. (2002). Platform leadership: How Intel, Microsoft, and Cisco drive industry innovation (Vol. 5, pp. 29-30). Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

[7] Gawer, A., and Cusumano, M. A. (2014). Industry platforms and ecosystem innovation. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(3), 417-433.

[8] Thomas, L. D., & Autio, E. (2019). Innovation Ecosystems. Available at SSRN 3476925.

[9] Komninos, N. (2020). Smart Cities and Connected Intelligence: Platforms, ecosystems and network effects. Routledge, Regions and Cities series.

[10] Von Hippel, E. (2017). Free Innovation. MIT press.